by Tom Minnon, LEED® AP, CDT, Eastern Region Sales Manager for Tubelite Inc.

The International Green Construction Code (IgCC) is the first national green model code. It is flexible, enabling jurisdictions to choose additional requirements that make the code a deeper shade of green, while paying close attention to the local climate and local regulatory requirements.

This new code is intended to provide “minimum requirements to safeguard the environment, public health, safety and general welfare;” to reduce the negative impacts and to increase positive impacts of the built environment on the natural environment and building occupants. As such, it covers natural resources, material water and energy conservation, operations and maintenance for new and existing buildings, building sites, building materials and building components (including equipment and systems). The IgCC applies to all occupancy-types, except low-rise residential buildings under the International Residential Code.

The IgCC can have a major, immediate impact. According to the Energy Information Administration, buildings generate almost 40 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions and 76 percent of all power plant generated electricity. Buildings can, and should, be designed to operate with significantly less than today’s average energy levels.

How does this complement existing rating systems or other guidelines?

Rating systems, such as LEED, are voluntary guidelines for cutting-edge applications of green building design. The IgCC establishes minimum requirements for all buildings, providing a natural complement for voluntary rating systems that extends beyond the IgCC’s baseline. Rating systems are voluntary. In contrast, a model code adopted by the jurisdiction is enforceable and has the weight of law. The U.S. Green Building Council, creator of LEED, has participated in the development of the IgCC and endorses its usage as a viable option for communities that wish to regulate minimum green building provisions.

To fully appreciate the position of the IgCC in the advancement of building performance, it is important to understand the distinction among three modes of regulation: prescriptive, performance-based and outcome-based.

* Prescriptive codes, as the term suggests, prescribe specific materials, systems or configurations, such as the R-value of insulation or the percentage of exterior surface that may be glazed.

* Performance-based codes establish performance expectations, such as a maximum amount of anticipated energy use, and proposed building designs demonstrate compliance with these expectations through computer modeling. The IgCC offers both prescriptive- and performance-based paths to compliance.

* The third, emerging mode is outcome-based. While performance-based methods predict — but do not absolutely ensure — a level of performance, an outcome-based code would require that a building actually perform to expectations as determined through the monitoring of the completed building in operation.

Prescriptive vs. Performance Paths for Energy Compliance

The prescriptive path is a set of pre-determined, simple and easy-to-follow guidelines and assembly performance values that address energy performance features in the design of a building. They do not require extensive analysis or technical support. Intended to be easily understood and applied, prescriptive requirements are basically a building assembly component checklist of required performance values that, when applied, will be accepted as having met the minimum code requirements.

The performance path defines a process by which an architect can design a building that will achieve energy code compliance with custom architectural assemblies, energy values and features, instead of a set of prescribed values. On the performance path, energy modeling is required to demonstrate that the overall reduction in energy use of the proposed building is at least as good as the minimum code requirement.

In response to the need for greater energy conservation, prescriptive path elements continue to become ever more restrictive to the point of significantly limiting design flexibility. And while relatively simple, the prescriptive path also doesn’t provide the flexibility needed to respond to integrated passive design strategies, such as maximizing daylight, strategic window placement or evaluating trade-offs of view-glazing placement with higher thermal performance assemblies.

Some examples of the fenestration limitations of the prescriptive path are:

- Mandatory values for solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) and window performance may not necessarily be beneficial in all climate zones, where in certain instances, solar gain coming into a building can offset heating needs. Restrictions on the amount of glass and SHGC requirements also severely limit daylight penetration that can afford reduction in electric lighting and associated cooling energy consumption.

- The prescriptive path of the IgCC mandates that solar shading devices be permanently attached on specified building orientations; however, successful design of solar shading is likely better suited to the flexibility in the performance path rather than the prescriptive path.

- The amount of glass on a building is restricted in the prescriptive path. For example, if a designer or building owner wants more transparency, or wishes to take advantage of views or unique site opportunities, the potential to compensate with higher performance in other building assemblies is only available using the performance path and energy-modeling. The performance path affords much greater freedom of design choice. It affords the opportunity to offset different system efficiencies against others, so long as the overall energy efficiency goals are met.

On-Site Renewable Energy Systems

Building project design shall show allocated space and pathways for future installation of on-site renewable energy systems and associated infrastructure that provide the annual energy production equivalent of not less than 6.0 kBtu/ft2 for single-story buildings and not less than 10.0 kBtu/ft2 multiplied by the total roof area in ft2 for all other buildings.

Daylit area of building spaces

IgCC has very specific requirements for daylighting a building. The designer must take into account any side-lighting (vertical fenestration), rooftop monitors, skylights and tubular daylighting devices. A daylight analysis must be conducted that includes:

- Exterior shading devices, buildings, structures and geological formations on the fenestration of the proposed building and on the ground and other light reflecting surfaces.

- Movable exterior fenestration shading devices.

- Blinds, shades and other movable interior fenestration shading devices.

- Automatic daylight controls.

- Dynamic glazing.

Permanent Projections

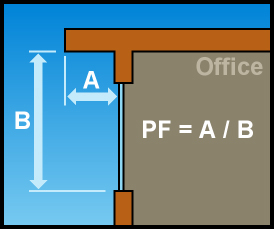

For climate zones 1–5, the vertical fenestration on the west, south and east shall be shaded by permanent projections that have an area-weighted average Projection Factor (PF) of not less than 0.50. The building is allowed to be rotated up to 45 degrees to the nearest cardinal orientation for purposes of calculations and showing compliance. The PF is the ratio of the distance the overhang projects from the window surface to its height above the sill of the window it shades.

[Courtesy of www.energycodes.gov]

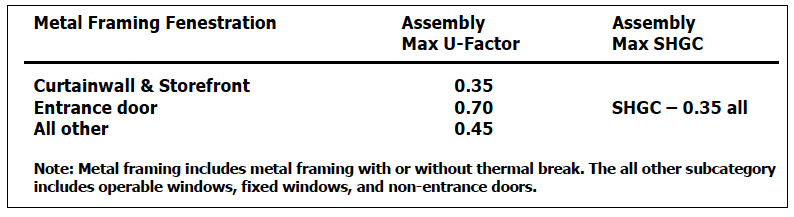

[Courtesy of www.energycodes.gov]

Vertical Fenestration Area

The total vertical fenestration area shall be less than 40% of the gross wall area. This requirement supersedes the requirement in Section 5.5.4.2.1 of ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1. Keep in mind that the vertical fenestration of a building may be allowed to exceed 40% by using the Performance Path for energy compliance.

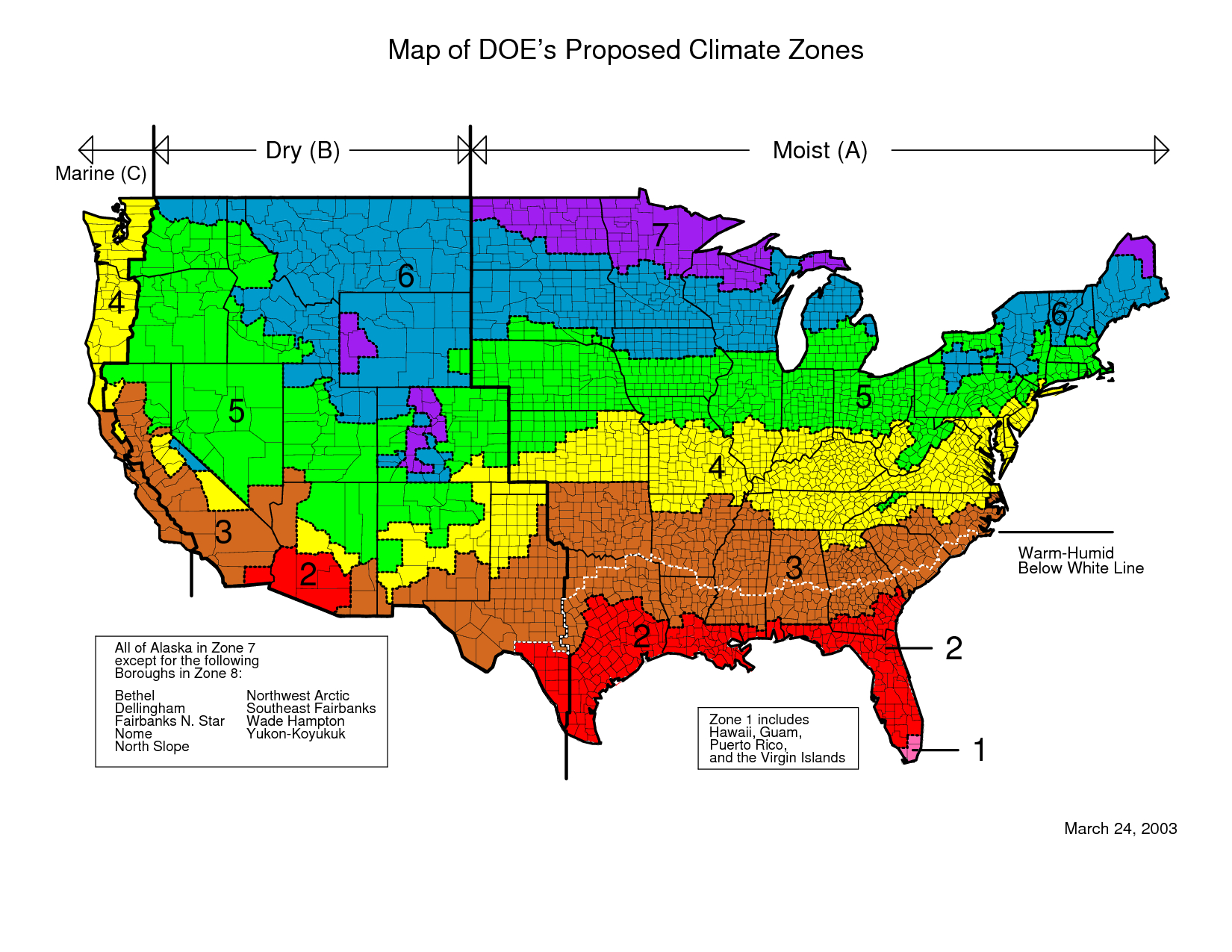

Maximum U-Factors and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient

The table below shows the U-Factor and SHGC requirements for climate zone 5 per the IgCC (in green on the map below).

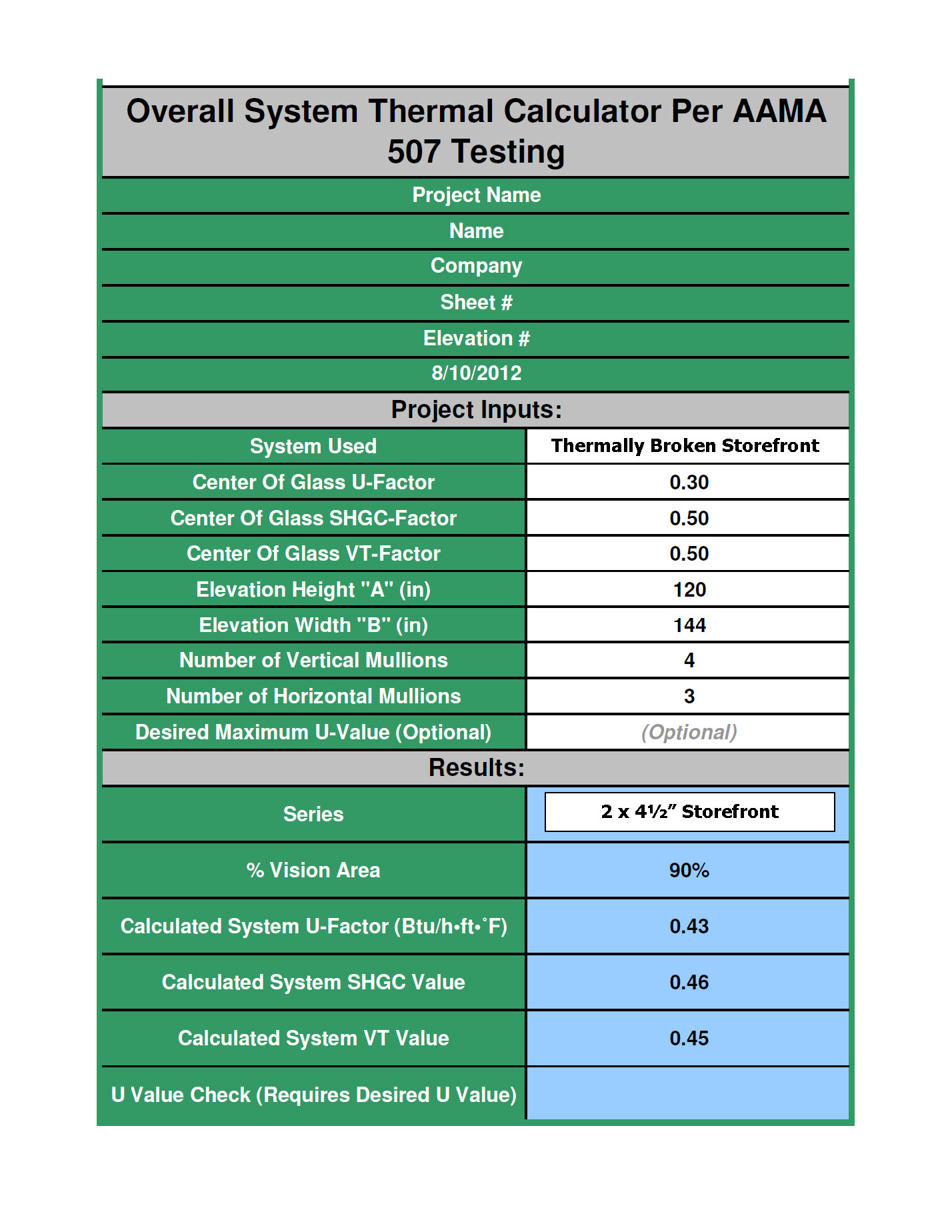

These performance requirements present a real challenge to the architectural aluminum industry. Many manufacturers are responding to the need for more energy efficient glazing systems by developing new and improved thermal break technology, such as: double pour and debridge, thermal strut and curtainwall fiberglass pressure plates.

The thermal analysis below shows that using standard storefront with a single thermal break and glass with a Center of Glass (COG) U-Factor of 0.30, does not meet the “Assembly U-Factor” code requirement of 0.35 of less.

The adoption of the IgCC is a step toward achieving the goal of carbon neutrality in building construction by 2030. The IgCC is the first model code to include sustainability measures for the entire construction project and its site — from design through construction, certificate of occupancy and beyond. The new code is expected to make buildings more efficient, reduce waste and have a positive impact on health, safety and community welfare. We will all need to become more familiar with this new code as it gets adopted by states and municipalities.

The adoption of the IgCC is a step toward achieving the goal of carbon neutrality in building construction by 2030. The IgCC is the first model code to include sustainability measures for the entire construction project and its site — from design through construction, certificate of occupancy and beyond. The new code is expected to make buildings more efficient, reduce waste and have a positive impact on health, safety and community welfare. We will all need to become more familiar with this new code as it gets adopted by states and municipalities.

**

Resources:

The American Institute of Architects’ Guide to the IgCC, http://www.aia.org/advocacy/AIAB085336

International Code Council (ICC) and the IgCC, http://www.iccsafe.org/cs/IgCC/Pages/default.aspx?r=IgCC

ICC PowerPoint – Overview of the 2012 IgCC, http://www.iccsafe.org/cs/IGCC/Documents/Media/2012_IgCC-Overview.pps

ICC Book – Green Building: A Professional’s Guide to Concepts, Codes, and Innovation, www.iccsafe.org

Windows for High Performance Commercial Buildings, http://www.commercialwindows.org

**

Tom Minnon, LEED® AP, CDT, is the eastern region sales manager for Tubelite Inc., serving clients from Maine to Georgia. With nearly four decades of industry experience and many professional accreditations, he regularly provides educational and consultative support to architects, buildings owners and glazing contractors regarding storefront, curtainwall, entrances and daylight control systems.

###